Part 1: The Day Putin Killed 186 Russian Children

The Beslan tragedy still lives, but Putin has killed and imprisoned people to make Russians forget about it

On September 1st, 2004, 1100 people went to the school in Beslan in the Republic of North Ossetia Alania. It lies a mere 50 kilometers from Ingushetia. North Ossetians and the Ingush are historical enemies. In 2004, Ingush terrorists crossed the border and seized the grammar school in Beslan.

Was it an act of revenge for the violence committed against Ingush men in 1992 when they were executed by Beslan locals or just part of the never-ending insurgencies in the North Caucus mountains? It is really anyone’s guess.

What was suspected then but is evident to many now, 19 years later, the tragedy in Beslan was both a well-articulated and damning assessment of the corruption that rules Russia and it was a tragedy that indeed could have been stopped by Putin and his FSB but was likely permitted to play out so Putin could impose his will on the country under the slogan, “a little less democracy and more safety is what Russia needs.”

After watching what happened in Beslan, few living in Russia could argue that self-expression was great and all that, but blowing trains and killing kids had to stop. Putin was granted a mandate for the Russian people — “Do what needs to be done to stop this. Even if it means you need to curtail our rights.”

The Beslan tragedy didn’t unite Russia. Russia is not the kind of country that unites around much. It did, however, show us anyone paying attention then, and years later, how Putin was going to unravel the “freedoms” of the post-Soviet period and how he was going to pull everyone who dared slip away from Moscow’s control back into the fold — even it killed them.

What transpired in Beslan happened because of Russia’s colonial attitude toward the republics, both the ones that slipped away in 1992 and the ones still part of Russia today.

The event had security and political repercussions in Russia, leading to a series of federal government reforms consolidating power in the Kremlin and strengthening the powers of the President of Russia. Criticisms of the Russian government’s management of the crisis have persisted, including allegations of disinformation and censorship in news media as well as questions about journalistic freedom, negotiations with the terrorists, allocation of responsibility for the eventual outcome, and the use of excessive force (Beslan School Seige)

Bad luck Vlad

From the moment Vladimir Putin came onto the radar of Russian history, blood has been pouring freely from the bodies of innocent men, women, and children all over Russia, the former Soviet Union, and even in the “Near East,” as Russia calls Syria.

An insatiable killer, his appetite for death has ruined the lives of thousands over the last 24 years. It began with the bombings of apartment blocs in Russia, killing hundreds of sleeping Russians, followed by the sinking of the Kursk — technically not his fault but just part of his bad luck — and continued with a war in Chechnya, countless metro and airplane bombings, the murder of innocent Syrians, and now the genocide of Ukrainians.

The following is a minute-by-minute account of September 1st, 2004. It was prepared by a Beslan survivor’s group in Russia that refuses to let the country forget this day — even though the government has done everything it can to forget. September 2nd and 3rd will follow in Part 2.

Over the years, survivors have been arrested for seeking medical and psychological treatment. Survivors have been harassed by the FSB and police. Putin wants the tragedy of Beslan to go away because it is both a symbol of the rot of Russian society and, most likely, it was an operation carried out in part with the participation or tacit acceptance of the dark forces that rule Russia today.

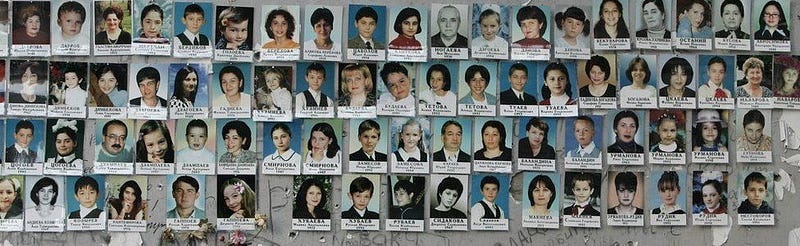

Of the 314 people who died as a result of the hostage-taking, 186 were schoolchildren who had shown up to celebrate the new school year. Most of the dead were killed when Russia’s security forces assaulted the school — what heroes, right?

The night before the Beslan attack, a female bomber, a “shakhidka,” wearing a belt bomb, blew herself up at a central Moscow train station at 9:30 p.m. 10 people were killed and 50 wounded.

Here are the voices, and actions of many bravewomen, children, and men who died and survived in Beslan on a beautiful September morning at the beginning of the school year.

September 1, 2004 — The South of Russia

The GAZ-66 (a Russian truck) with terrorists makes its way to Beslan along field roads. In the area of the village of Khurikau, the truck catches the eye of the district police officer Sultan Gurazhev.

The truck seems suspicious to him. The policeman gets on his tail and demands it to stop. He flashes his headlights, honks, and overtakes him.

Finally, the GAZ-66 stops. The police officer approaches the driver and asks him through the slightly open window:

- Why didn’t you stop? Why don’t you react? Where are you driving?

The driver doesn’t answer.

The policeman wants to repeat the question, but at that moment, militants in camouflage and masks attack him from behind, tie his hands, and throw him into the back seat of his car.

“Take away the weapons,” says one of the terrorists in the Vainakh language.

The gang acquires trophies — a Zhiguli model #6, a typical police car, and the service pistol of the district police officer Gurazhev.

- Let his car drive ahead! — the leader Ruslan Khuchbarov commands.

The terrorist truck continues to move towards Beslan. Along the way, it won’t stop anywhere else

The principal of Beslan School №1, Lidiya Tsalieva (pictured), admires the fresh renovations in the building. “The smell of paint! Lovely! The soul rejoices!” — she thinks.

Previously, the school had a panic button for security. A month before, it was removed because it became unusable during repair work.

Marina Dudieva, sister of first-grader Dzerassa Kudzaeva, takes a taxi to the nearby city of Vladikavkaz. She must pick up a cameraman to film the official ceremonies at school №1 on that day. On the way, they often come across cars with license plates from Ingushetia, which is in Chechnya.

“I didn’t even think that the school could become the target of an attack,” he admits in court.

Doctor Larisa Mamitova (pictured), working in an ambulance, returns from her night shift. Her son, 7th grader Tamerlan, is going to school №1. Larisa barely persuaded him to go to the official ceremonies or the “first call.”

“He doesn’t like these events: neither September 1st nor the ceremonial last call before graduation,” explains Mamitova.

Tamerlan and his mother, Larisa, are walking towards the school. She notices that, unlike in past years, there is no traffic police car here today.

What, Tamik? Are there none this time? — Larisa asks her son.

Oh, they’re on the highway somewhere! — Tamerlan jokes in response, not suspecting anything.

The traffic police crew, which was always on duty at the school, is actually on the highway. The motorcade of North Ossetian President Alexander Dzasokhov is scheduled to pass there.

The school is guarded by a single police officer, Fatima Dudieva (pictured). Astoundingly, she has no weapon.

“We women are not given weapons,” she explains.

Student Zalina Dudieva goes out onto the balcony. You can hear from the balcony that there a real holiday in the courtyard of school №1 is underway. From the neighboring balcony, her neighbor Olga Dzgoeva calls out to her (in the photo):

— Zalina, let’s go! The music is playing very loud! This year will probably be fun! Zalina agrees.

Policeman Dudieva goes around the classrooms, congratulating schoolchildren and teachers on Knowledge Day. Suddenly, the mother of one of the students, Inga Basaeva-Chedzhemova, approaches her.

“Over there where the school territory starts — there is a suspicious KamAZ car,” she tells Dudieva — it was actually the GAZ-66 with the terrorists.

Policeman Fatima Dudieva leaves the school, where the first call is about to begin, and sees the same GAZ-66 nearby. There is no one in the cabin.

A suspicious truck near a huge crowd of children alarms Dudieva. She decides to go back to school and call her district department.

The ringing of three school bells starts the ceremonial line of students at school №1. Children leave their classrooms in an orderly manner. Teachers arrange the children into their respective classes.

Principal Lidiya Tsalieva takes her place on the school line. They give her a huge bouquet, but Lidia Alexandrovna doesn’t even look at it.

Her gaze is focused on her students: “These are flowers, this is joy, it cannot be described! I have never seen such beautiful children!” — she remembers.

To kick off the school year, balloons fly into the air. Larisa Mamitova hears claps. “Wow, they give fireworks to the children!” she smiles.

They are also heard by 11th-grader Zaur Aboev (in the photo), who has already picked up (It is tradition that the biggest child from the graduating class puts the smallest child on his shoulders and carries him (or her) around the field while everyone claps. My wife was carried around the field, and she says it was one of the most unforgettable moments of her life) first-grader Dzera Kudzaeva. “Who is messing around with fireworks?” —he thinks.

Policeman Fatima Dudieva enters the teachers’ room. She takes the phone to report a suspicious truck near the school to the district department. At this moment, nine people in camouflage and with machine guns burst into the office:

— Cop, where do you want to call? This isn’t going to be another “Nord-Ost!” (The Nord-Ost was another blunder by Putin’s security forces. A packed theater, Nord-Ost, in Moscow, was seized by terrorists during a show. The security forces filled it with an opiate-based sleeping gas to knock out the terrorists before assaulting it. 170 people died from the gas.)

The school line is surrounded by militants in camouflage, shooting in the air.

- What is this? Classes have started already, or what? — thinks Larisa Mamitova. There is a police station right next to the school, and many cannot even imagine the thought that they are actually being taken hostage.

— Everyone inside! — the terrorists shout.

More than 1,000 students, parents, and teachers are herded into the school gym. Almost no one resists.

“It’s amazing how a person begins to obey in such moments. You don’t hear yourself, only what is driving you. It feels like you want to run to please them,” recalls the 9th grader, Stas Bokoev.

But several people still try to escape so as not to be taken hostage. The terrorists opened fire on them.

“They shot at the legs of those who ran away. Next to me in the hall sat a woman with a bullet in her leg. I don’t know if she survived. “I don’t even know the name,” recalls the hostage, Alla Khanaeva.

Regina Kusaeva is looking for her 9-year-old Izeta in the crowd of hostages.

— Was anyone killed in the yard? “I’m looking for my daughter,” she asks the terrorist.

— Come into the hall, we didn’t kill anyone. Now you will find your daughter. And my daughter was killed like this. I will never find her again.

A car drives up to the school. Ruslan Fraev jumps out of it, having just learned about his children being taken hostage.

The father is eager to go to school. Terrorists fire at him from the windows.

Fraev was killed. The body of the first victim of the terrorist attack in Beslan will lie on the ground for three days.

Employees of the Pravoborezhny police department, located 300 meters from the school, hear shooting. They get weapons and run towards the school.

— We couldn’t approach because there was shelling there. And the approaches to this school were shot through. “We took up defensive positions,” their boss Elbrus Nogaev will tell at the trial.

The question arises: why didn’t they die? Well, they didn’t die; they didn’t become heroes posthumously! — Elbrus Nogaev, the head of the police department, will throw up his hands in court.

“Not a single policeman approached the building,” the victims will reproach him. — Everyone was afraid.

“Probably because each one of them wanted to live,” he answers matter-of-factly.

A stream of people brings Doctor Larisa Mamitova and her son into one of the classes. Some parents hide their children under their desks, others try to call home.

“Dial the police,” advises Mamitova.

Attempts to call are interrupted by a militant:

— Throw away your phones! If I hear a ring on someone, I will shoot them.

There is panic and deafening noise in the gym. “No one can calm anyone down,” recalls hostage Larisa Tomaeva.

Sitting at the very edge of the crowd is the father of two, Ruslan Betrozov. The terrorists force him to stand up:

If there is not deathly silence, we will shoot you!

Betrozov asks people to calm down. “He calmly asked, begged us,” recalls hostage Larisa Tomaeva. In vain. Betrozov is shot in the back of the head.

Mom, why did the nice man fall? — a child’s voice is heard.

— He felt bad with his heart.

Zemfira Agayeva, who was taken hostage with her children, is trying to calm down her 7-year-old son Zhorik (pictured).

- He killed him! — the boy shouts.

— No, they are making a movie, Zhorik.

— Why is it so real? And what is this pouring towards us?

— Raspberry jam, Zhorik.

The terrorists force the hostages to drag Betrozov’s corpse several times in front of the entire crowd.

“So that everyone can see that they can do this,” explains hostage Felisa Batagova. — They dragged him there, and they dragged him back the same way. They leave a trail of blood. Everyone is making noise, everyone is screaming and crying.

The militants force people to sit on the edges of the gym. Now, its middle acts as a corridor.

Terrorists begin to mine the school.

— Do not worry! If ours and yours agree, everything will be fine! You will sit quietly — we will let the children go now!

Larisa Kudzieva (in the photo) sits next to the wounded Vadim Bolloev. The terrorists put a bullet in him because he refused to kneel.

The woman screams at the militants, demanding bandages and water for him. One of them is getting tired of it:

— Are you the bravest one here? Let’s check…Get up!

Larisa gets up. The wounded hostage, for whom she demanded bandages, grabs the hem of her skirt, trying to hold her back.

The woman is sent to the corner of the gym, driven by a blow from a butt in the back.

— Get on your knees!

— I won’t get up!

The terrorists repeat their commands.

— I already told you, I won’t get up!

The terrorist puts a machine gun to Kudzieva’s head. She instinctively grabs the barrel and pulls it away from herself.

— There are women and children here; they are already so scared! By the way, your children rest in our sanatoriums, and your wives give birth in our maternity hospitals!

— These are not ours, but Kadyrov’s spawn!

A militant with a bandaged hand approaches the noise:

— What’s happening?

Larisa Kudzieva once again asks for water and bandages for the wounded man.

— Sit down! — the terrorist orders. — You will get nothing.

— Your hand is bandaged. Give me a bandage too!

— Shut up! Go to your place.

Reaction of the town

Among the 35,000 residents of Beslan, there is not a person who does not have a relative or at least an acquaintance in the seized school. The first reaction of the townspeople is caught on an amateur video camera. Women sob, falling to their knees and breaking into screams.

One of the terrorists shows the hostages in the gym an explosive device:

— Look at this little thing. There are 17 thousand fragments here. Sit quietly! If the assault begins, we have weapons to shoot back for five days. On the sixth day, we blow everything up.

Muscovites, who do not yet know about the seizure of the school in Beslan, are mourning those who died at the Rizhskaya metro station. Flowers are brought to the entrance, and candles are lit.

Albina Vasilievna, who works near the metro, is indignant:

— I’m horrified’ by what’s happening! Defenseless, simply useless people!

Terrorists recruit men to bomb the gym. Artur Kisiev (pictured) flatly refuses: “So that I kill children with my own hands!”

He is taken away to be shot. Finally, Arthur asks teacher Raisa Kibizova-Dzaragasova to look after his son and, with a long, silent stare, says goodbye to him.

Left in the hall without his father, seven-year-old Aslan Kisiev crawls up to his teacher Raisa Kaspolatovna.

-Where is Arthur? — he asks.

“I was surprised that it wasn’t, ‘Where’s daddy?’ I think he understood everything, but he was afraid of the truth,” recalls Raisa Kibizova-Dzaragasova.

One of the terrorists walks around the gym and asks:

— Is there a doctor among you?

Emergency doctor Larisa Mamitova rises from her seat. The militants take her out into the corridor and take out medicines from their backpacks:

We have wounded. Bandage them.

One militant was slightly wounded in the arm, but the second had a bullet lodged in his stomach. He is already pale and is losing consciousness. Larisa Mamitova understands that he can no longer be helped but still tries to take care:

- Actually, he needs to be put to bed.

No place to lie down. “Let him sit,” the terrorists answer.

Why did you take the children? — asks doctor Larisa Mamitova, bandaging a terrorist wounded in the arm. — You have some requirements.

— One demand: withdraw troops from Chechnya.

— Let me go out and make your demands.

— Mind your own business! Do what you are told and be gone!

“There are many children here under six years old who should not have been in school at all,” Mamitova insists. — For their sake, let me go out.

“I don’t decide anything,” answers the wounded terrorist. — “The Colonel” decides.

- Well, put me in touch with the Colonel. Maybe he will allow it?

Okay, I’ll be back.

Residents of Beslan, who learned about the seizure of the school, are trying to break through the police positions to save their children.

- Let me in, I have a child there!

— My beloved grandson!

Some even manage to run a few steps towards the school, but are forced back.

The bandaged militant returns to Larisa Mamitova:

- Sit here. “Colonel” will do. One step outside the gate, your son will be killed,” he begins to instruct the parliamentarian. — If you take a step outside the gate, they will kill you too.

— I’ll come back. I won’t leave my son here.

President of North Ossetia Alexander Dzasokhov (pictured) arrives in Beslan. It was his motorcade that distracted the traffic police crews, leaving the school unguarded.

An operational headquarters under his leadership begins to operate in the local administration.

Head of Parliament Teimuraz Mamsurov arrives with the President of the Republic. He is openly distraught. His son and daughter are at school.

“My children were there. It was impossible to contact them. They didn’t have telephones. Ten-year-old children — what kind of phones could they have?” — recalls Mamsurov.

The country learns about the terrorist attack in Beslan. The Rossiya TV channel states that “at least two hundred” children have been captured. In fact, it’s many times more.

The terrorists allegedly “categorically refuse to negotiate with the authorities,” although no one had yet had any contact with them at this point.

The men of Beslan, having learned about the capture of their loved ones hostage, take out hunting weapons and begin to gather around the school. In order for police and military personnel to distinguish them from militants, they wear white bands on their sleeves.

Journalists will call the armed locals militias.

A tight cordon is being set up around the captured school. Soldiers are pushing back a crowd of relatives towards the Palace of Culture.

“The Defenders of the Fatherland (the soldiers) are so small, frail, and thin as if they were not fed. Their necks are like matches,” observes journalist Murat Kaboev.

For the next four and five hours, officials are arriving by plane from all over Russia. The well-known journalist Anna Politkovskaya, known for her anti-corruption and human rights work and always a thorn in the side of Putin, has been asked to escort officials from Ingushetiya. They want to use her as a shield so they won’t be attacked or arrested by Russia’s FSB. Politkovksaya was assassinated in Moscow two years later. No one doubts that it was Putin who killed her.

Larisa Mamitova exited to the authorities with a note from the terrorists and on it they wrote the wrong phone number. No one from outside could reach them. As the students sat without water and with their hands over their heads, parents tried to calm them by explaining that all that was going on around them was just a movie.

Fighting between the terrorists

At 3 p.m., six hours after the taking of the school:

Hostage Alla Khanaeva witnesses an altercation between one of the suicide bombers and the terrorist leader Khuchbarov.

- No, no, I won’t! You said it was the police department! — She raises her voice and throws her gun on the floor.

- Let’s go out.

They go out. Machine gun fire sounds

The second suicide bomber runs away from the terrorist leader into the classroom. A powerful explosion is heard. Two of the male hostages, kneeling in the corridor, fall dead. Six more were seriously wounded. They writhe in pain.

Opposite the door to the classroom lies one of the terrorists. He was wounded in the stomach.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs asks the administration for the number of students in school №1. They answer that there are 800 of them.

None of the security forces is ready to take responsibility for such a figure (never can they take responsibility for anything). The headquarters appeals to relatives of the hostages with a request to file reports of the disappearance of each individual person (even here, Russia’s bureaucracy proves that it is always more responsible and powerful that the average man).

But relatives are already compiling their own list of hostages, where they are listed by name. It turns out to be the most accurate and has 1,080 people.

The townspeople submit the list to the security forces headquarters.

After another news broadcast on TV, the leader of the militants enters the gym:

— Your Putin underestimates us! We will show him the seriousness of our intentions. The terrorists raise several more men from their seats. They are taken out of the gym and forced to sit on the floor in the hallway.

Businessman Aslan Kudzaev is sitting on the floor with other men. The gunman counts out 10 people and orders them to enter the classroom. But when the eighth man comes in, he blocks the door with his hand: “Stop.”

Kudzaev and another man remain in the corridor. Shots are heard from the office.

It is finally learned that the number given by the terrorists was wrong. The situation is cleared up when the doctor, Larisa, pleads with the terrorists to take the corrected number out. Finally, the authorities make contact.

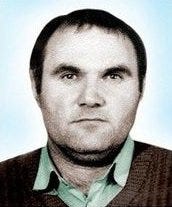

FSB negotiator Vitaly Zangionov (pictured) calls the indicated number. A terrorist nicknamed “Shahid” is in touch:

“I shot 20 people and blew up another 20,” he inflates the numbers. — If within 3 hours you don’t provide us with Aslakhanov, Roshal (child psychiatrist), Zyazikov and Dzasokhov, I will shoot 20 more.

Despite the situation, everything in Russia is still pretty much the same

As is so very typical of Russia, in the immediate aftermath of the bombing in Moscow the night before and then the taking of the school, the media announce how the security forces are “locking the country down.” Heightened security is everywhere and the border between Ingushetiya and Russia has been closed. Beslan also had supposedly been cut off from the rest of the country by the police and military.

Yet, while measures were taken, nothing can’t be overcome in Russia by a wink and a few dollars.

A GAZelle (A type of Russian truck used for deliveries) with journalists Olga Allenova, Valery Melnikov, and Eduard Kornienko has been stuck in a traffic jam to enter Ossetia for an hour.

Two guys come up, and for 200 rubles, they promise to drive the car ahead of the queue:

— Usually, the price is less. But you see what day it is. 50 rubles must be given in advance.

The GAZelle with journalists drives around a traffic jam. The driver speaks to the guard, and the car is allowed through the barrier. No one checks the car, the bags, or the passports of the passengers.

“The cynicism of Russian ‘illegal tax collectors’ shocked me,” recalls Kommersant correspondent Olga Allenova (this, folks, is the essence of Russia).

You made it, the escort tells the driver of the journalists;

— Now just hurry up and give me the money.

They ask if Beslan is closed.

— I can accompany you to Beslan. Pay 1,200 rubles,” the guy quickly comes up with an amount. — No? Well, go yourself. Everything there is closed; they won’t let you in.

The journalists give the escort more money. He gets into his old “Zhiguli #9” and orders us to follow him to Beslan. During the entire journey, we saw only two traffic police cars. They didn’t stop us. In Beslan, the road was blocked by police patrol cars, but they didn’t stop us either,” writes Olga Allenova.

One hostage has a small child crying in her arms in the gym. She fails to calm him down.

The nearest militant first aims at her — and says, calm it down. But then he takes a deep breath and takes out a bottle:

— This is my water; give it to the child. And two more candies. Let him suck through the handkerchief.

The young mother is afraid that the terrorist will poison her child, but teacher Raisa Dzaragasova-Kibizova convinces her:

— We still can’t leave here alive, even if the child calms down now.

Half of one “Mars” bar goes to the baby. The remaining one and a half go to other older children.

Hostage Larisa Mamitova (the doctor) listens to terrorist Khodov’s lectures:

— Our women and our children are being killed! Why did you, who live next to us, never come out and hold a rally in defense of us? Our women make sacrifices: They blow up planes and trains.

Why didn’t you get up and go to the rally against your government’s crimes against us (sounds very familiar to the genocide today in Ukraine)?

The GAZelle, with journalists who paid 1,200 rubles for passing through all checkpoints, approaches Beslan at a speed of 100 km/h.

“We drove almost nonstop, never once being examined at any checkpoint, on the day when the militants took about 1,200 hostages,” recalls Olga Allenova.

Journalists approach the cultural center. There are women sitting on its steps. One of them howls quietly. Others scold her: “You’re inviting trouble (Russians put more faith in such superstitions than they do in the failings of their government).”

“My sister Rosa is at my school,” resident Zinaida Tedzoeva tells Olga Allenova. “Do you think that if they turn on the gas, like in Nord-Ost, will there be any survivors?”

A Kommersant (Russian business newspaper) photographer takes pictures next to the BTR Palace of Culture with riot police.

— Send these photos to Putin and tell him thank you from North Ossetia! — one of the policemen says angrily.

— For what? — journalists ask.

— For Chechnya.

Even with a tragedy, Putin still finds time to be Putin

The human rights journalist Anna Politkovskaya, was requested to be involved by the Ingush separatist leader. The hope was that her presence would keep him safe. Politkovskaya, however, by 2004, four years into the Putin nightmare, was already a thorn rotting in the side of Putin. Russia still had not shaken off the effects of post-Soviet democracy, and there was still a fair amount of independent journalism being done.

Putin’s plan to put an end to democratic yearnings and crush any hopes for building a vibrant civil society was well underway. The likelihood that Beslan was of his long-term goal is great. As fear of terrorists rippled through the country, an unseen president — this is Putin’s modus operandi when bad things happen, he vanishes and lets others become the face for his evil doings —the time had come to deal with the vestiges of Russia’s bold, 1990s journalism.

Journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who agreed to be a human shield for separatist leader Aslan Maskhadov, flies from Moscow to Rostov-on-Don. She refuses meals on board and only orders tea from the flight attendant.

Politkovskaya drinks a cup of tea.

Half an hour after drinking tea, Politkovskaya begins to lose consciousness. The last thing she manages to do is call the flight attendant.

“After that, some fragments remained in my memory — the flight attendant was sobbing and shouting: “Hold on, we’re going to land!”,” the journalist recalls.

The plane Politkovskaya is flying on is landing. At this moment, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Novaya Gazeta Sergei Sokolov’s phone rings:

“Seryozha, I feel bad… Seryozha, I’m losing consciousness…,” the journalist’s voice is heard on the phone.

The editor-in-chief of Novaya (Russian newspaper), Dmitry Muratov, calls a friend of the newspaper — the head of the FSB department for Chechnya, stationed in Rostov-on-Don, Sergei Solodovnikov.

“Muratov said that some kind of accident happened to Anya there. we need to drive up and figure out what’s wrong,” recalls the security officer.

Anna Politkovskaya is carried out of the plane. This is being monitored by the head of the FSB department for Chechnya, Sergei Solodovnikov.

“I saw a terrible thing. She was in a semi-conscious state,” he recalls.

The journalist is taken to the Rostov regional hospital.

At the same time that Politkovskaya is being poisoned, on Russia’s main TV station, Mikhail Leontiv, a television journalist, calls the terrorists animals and killers who deserve nothing short of death. Leontiv made similar statements at the height of the Nord-Ost theater hostage crisis. Aware that the terrorists are watching the television looking for messages of potential official actions, Leontiv is pushing them to act.

Leontiv also makes a statement that would become the backbone of Putin’s policies going forward. He says that the spate of terrorist attacks are clearly organized by the West. Led by the U.S., the West fears a strong and united Russia. Leontiv tells Russians that in order to preserve Russia and keep it strong to fight off its enemies, it needs a totalitarian form of government.

Putin is unveiling his plans for Russia and while no one fully understands what is being said, heads all over the country are nodding affirmatively because no one likes seeing the kids being held hostage by terrorists.

Mikhail Leontyev insults the Chechen separatists throughout the country. As during “Nord-Ost,” he does this exactly at the moment when the FSB is trying to negotiate with them.

This time, Leontev goes even further: he blames the West for the terrorist attack and talks about the advantages of a totalitarian system.

Anna Politkovskaya regains consciousness in the Rostov regional hospital. “Welcome back!” — she hears.

The nurse tells the journalist that when she was brought in, she was almost hopeless: “Darling, they tried to poison you.”

One more journalist was assigned to act as the “shield” for the separatist leader Maskhadov, but as he awaits a plane to take him to Maskhadov, he is arrested for drinking a beer in public — it was a new law in Russia that no one was enforcing. Maskhadov is unable to go to the terrorits which further upsets them.